DEEP-SEA BIOLOGY

|

|

| NOTE: if you use or copy any pictures, please writer for permission (see MAIN PAGE for instructions) |

DEEP-SEA BIOLOGY

|

|

| NOTE: if you use or copy any pictures, please writer for permission (see MAIN PAGE for instructions) |

|

III. Deep-Sea RESEARCH AT SEA:

updated 8/06 with Alvin

information; see new VENTS page

for 2007-08 Alvin photos

|

| EQUIPMENT FOR DEEP-SEA BIOLOGY A. SHIPS AND NETS: Studying the deep sea requires properly outfitted research ships (R/V for research vessels), with cranes and winches. Examples of ones we have used are the Wecoma of Oregon State Univ., the Thomas G. Thompson of Univ. Washington, and the Atlantis of WHOI . --Research with trawls and dredges is a round-the-clock process. It involves hours of free time as the net goes down then up. During this time we analyze samples and data, sleep, eat, or relax with books, movies, games, watching the sea. This is followed by intense teamwork when the net returns as the fishes and invertebrates have to be sorted, dissected, analyzed and preserved before they decay. See pictures below. B. SUBMERSIBLES: 3. Relatives of the ROVs are the AUVs (autonomous underwater vehicles)--self-propelled robots carrying instruments that can rove the seas for long periods. 4. Other information: D. CAMERAS and OTHER PERMANENT INSTRUMENTS: Other deepsea research is using cameras and other instruments on platforms on the seafloor, or on buoys at the surface. Examples: Mbari's Ocean Observing System (MOOS), the New Millenium Observatory (NeMO) on the Juan de Fuca ridge, and the Neptune Undersea network off western USA and Canada. E. LANDERS, CORING DEVICES, WATER SAMPLERS, Etc.: There are also a variety of other devices which can be deployed into the deep with a crane and winch on research ships, or dropped free-fall to the seafloor (to be retrieved by sending a sonic signal to tell the device to release its weights). One example is a multicoring device (picture above) which plunges into the seafloor and collects cores of sediment. Another is a Conductivity-Temperature-Depth (CTD) sensor and water sampler (see picture, above). Both of these remain tethered to the winch cable. There are also specialized free-falling LANDERS and ELEVATORS: see HADAL PAGE for examples |

|||||||

| Return to Top | Return to Contents Homepage |

|

|

|

|

|

| 1.

Operating otter trawl (1996/2009) After deploying the "otter" trawl, we took 2 hours to feed 6000m (almost 4 miles) of cable out to insure the net hit bottom at 2900m. Then we trawled on the bottom for 2 hrs, then took another 2 hrs to haul it in |

2. Sunrise at sea

(4/97) --we work around the clock in "watches" (like shifts on land) when trawling or using an ROV. |

3. Sunset at sea

(4/2014, South Pacific) --I thought I saw the famous "green flash" after one sunset. However, astronomer Andrew Young of SDSU reports this flash, though often real, may sometimes be an illusion resulting from red sunset light bleaching out our red retinal cones, leaving our eyes to see yellow light as green (New Scientist, 20-June-98, p.5) |

4. Porpoises

"surfing" Dolphins and porpoises occasionally ride the ship's bow wave. In 1992 it was shown that this saves these animals considerable locomotory energy (of course, they may also be having fun!). Click SURFACE button at bottom of page to get more pictures and videos of porpoises in the wild |

5. Typical catch of abyssal invertebrates (sea cucumbers, seaspiders, shrimp, anemones, soft urchin, etc.), and rattail/grenadier fish from a deepsea trawl |

|

|

|

|

. . |

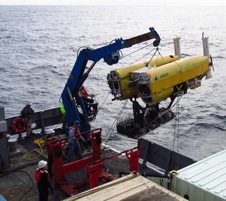

| 6. ROV

on deck of Thompson Oceanic Explorer sits on the deck of the ship, 2001 |

7. ROV launch --Nereus picked up by crane and lifted to the water, 2014 |

8. ROV manipulator at

work --arm collects specimens and experimental equipment |

9. ALVIN launch --the A-frame drops it slowly into the water, while swimmers (specially trained divers) wait in an Avon boat to remove the ropes |

10. Inside ALVIN -- 1 pilot and 2 "observers" fit snugly inside the titanium sphere, each with a porthole window...my first dive!* [photo of me by Tina Treude] |

. . |

|

|

|

|

| 11. ALVIN at work -- the pilot deftly uses the leftside manipulator arm to scoop up sediment and seep clams. During one dive, a cheeky squid attacks the arm! |

12.

ALVIN returns --swimmers reach the Alvin after it surfaces to get the sub ready for recovery |

13. Alvin Recovery 1

-- the swimmers perform the sometimes-dangerous task of hooking the A-frame ropes to the Alvin |

14. Alvin Recovery 2 --after securing ALVIN, the swimmers jump off the sub to swim back to the Avon |

15. Alvin "baptism" --after returning from your first dive in ALVIN, you are ceremoniously greeted with a bucket of icewater and a seawater hosedown [photo by Andrew Thurber] |

*MY FIRST ALVIN DIVE:

Although I have been doing deep-sea research for almost 25 years, until

2006 I had not been down in a research submersible because my deep-sea

research started on fish, which are much easier to catch by net than by

submersible. However, my recent work has been on invertebrates, and

submersibles and ROVs are great for collecting many of those. Thanks to

Chief Scientist Lisa Levin (Scripps), in July 2006 I spent 8 hours in

the Alvin, diving to 906m (about 3000ft) at Hydrate Ridge's East

Basin off Oregon. [See my Seeps and Vents

Page for more information and pictures.] Tina

Treude (USC) and I dove with pilot Gavin

Eppard. On the morning of our dive, it was touch-and-go on the

weather, as the winds were near 25 knots, the unsafe limit. Finally we

got the go-ahead. After we were sealed in and released

into the water, we bounced around in the high waves for a bit,

then Gavin flooded the ballast tanks and we began to sink slowly. It

took about 45 min to reach 880 m. During that time, in which the sub

lights are off, pure magic appeared out our windows as the sunlight

faded into night. The ocean became a galaxy of flashing lights, far more

than you ever see in videos! I could see luminescent jellies, squid,

4ft-long siphonophores, shrimp, and even fish blinking their headlights

as they darted by. [See my Midwater Page

for examples of these animals]

Finally we hit bottom and began our real work of collecting

tubecores of gas-oxidizing bacteria and methane hydrate, rocks,

and animals. Gavin was incredibly adept with the sub manipulators,

moving the tubecores in and out of the sub holders and seafloor sediment

with ease. We saw mounds of frozen

hydrate; grey, white and orange

bacterial mats; clambeds; carbonate

rocks; sponges; searobins,

eelpouts and hagfish; large Neptunea

snails tracking across the mud; and mushroom corals. As we worked, larvaceans,

ctenophores, jellies and fish drifted or swam past us. We also saw mysterious

rings that might be methane hydrate (frozen natural gas) in a form

that we've never heard described before.

About half-way through, the real prize appeared--a mysterious

transparent squid with tentacles sprouting up from its head rather

than in front as in 'normal' squid. I tentatively identified it as a

Teuthowenia-type squid. The creature stayed by us for several minutes,

allowing us a great look. As it got close to us, its head and tentacles

turned red, then it darted off across my window.

At one hydrate site, Gavin used the sub manipulator to grab a rock. Upon

our return, we found it to be a beautiful vent

rock, lined with crystalline chimneys through which gas once

bubbled. Later, he also grabbed a rock

composed mostly of shells.

Upon finishing our collecting at the designated target areas, we had an

hour of battery power left, so Gavin took us exploring down slope to see

if there were undiscovered hydrate sites. He let each of us take a 5-min

turn at the helm (actually, a joystick with 3 dimensions of

control). While I was driving, we did come across a large bacterial mat

around carbonate rocks. We eventually reached 906m before turning back.

Finally it was time to blow the ballast, drop the lead weights, and head

up. Gavin loaded Led Zepplin into the sub stereo, turned off the lights,

and again we rose through a luminescent fairyland. Finally we bounced to

the surface and found ourselves in high waves, seesawing madly. It took

some time to bring us safely aboard, and we found later that the winds

were above the safe level. Once secured on board, we climbed out, and I

was treated to the traditional bucket of

icewater on my head and a hosedown with seawater!

All told, the dive was one of the highlights of my life. I still marvel

at the skills of the pilot, swimmers, and all the other Alvin

teammembers...and the entire crew of the Atlantis. Working with

the other scientists was also a pleasure. My thanks to everyone!

ADDENDUM 2008: Thanks to collaborator Ray Lee of Washington State University, I dove again in Alvin in July 2008, this time to 2200m at the Faulty Towers hydrothermal vent field on the Juan de Fuca Ridge. This dive was truly otherworldly. Vent chimneys (known as white smokers) up to 70 ft (22m) rose above the seafloor spewing warm mineral-laden water. At the base of these towers, we came within sampling range of black smokers with water up to 600F (over 300C).

| Return to Top | Return to Contents Homepage |

| IV.A. HIGH PRESSURE and HIGH SULFIDE |

Movie of methane vent, near which hydrogen sulfide is produced by microbes |

PRESSURE: High hydrostatic pressure (from

the weight of the water column overhead) squeezes anything with an

air chamber, such as fishes with swimbladders. Many deep-sea fishes

do have fat-filled or vestigial swimbladders to avoid this problem,

but some do have air-filled ones. These require considerable energy

to inflate, and they expand (often lethally) when the fish is hauled

to the surface. Pressure does not cause large-scale compression of

most deepsea life due to the absence of air chambers, but it affects

all life at a microsopic scale. It forces water molecules to stay

densely bound to charged molecules, which interferes

with critical binding events in cells (such as an

energy-yielding molecule binding to an enzyme). For pressure

adaptations, see below.

The HIGHEST PRESSURES are found in the Challenger

Deep of the Mariana Trench in the western Pacific. This

trench is almost 36,000 ft or 11,000 m deep with almost 1100 atm

of pressure. The Mariana Trench has been explored by only 4

submersibles : 1) briefly by the manned sub Trieste

in 1960; 2) in the 1990s by a Japanese unmanned ROV, "Kaiko",

which was unfortunately lost

at sea in Sept. 2003; 3) by the US unmanned hybrid ROV Nereus

in

2009; and 4) by James

Cameron in his DEEPSEA CHALLENGER one-man sub in 2012. For

depth limits of submersibles and life, see the

Smithsonian's How

Deep Can They Go page, and Extreme

Science's Deep Ocean Creatures page. SULFIDE: Deep-sea animals at hydrothermal vents and gas seeps face another stress: high levels of hydrogen sulfide (H2S), a gas normally toxic to animals. However, giant tubeworms and certain clams and mussels at vents and seeps rely on sulfide-metabolizing bacterial symbionts in their internal tissues. Somehow the animals avoid sulfide toxicity--by binding sulfide to special proteins or converting it into non-toxic molecules. For our work on sulfide adaptations, see section 2 below. For pictures, see Seeps and Vents page |

|

|

|

|

| 1. Trawl and Alvin dive sites off Oregon; click here for schematic diagram. [3-D images of the seafloor can be see in Scientific American June 1997 (Oregon coast on p.84)] | 2. Styrofoam head before and

after a trip on the ALVIN Hydrostatic pressure increases by 1 atm with each 10m of depth. This shows effects of 50 to 90 atm pressure on a styrofoam head taken to 520m and 906m on the Alvin (images at same scale) |

3. Swimbladder decompression --a rattail hauled for 2 hrs to surface from 2000m. The air-filled bladder cannot be adjusted fast enough for low pressure, and it expands out the mouth. Eyes are also pushed out by expanding air. |

4. A transparent squid visits Alvin. Squids and most animals in the oceans do not have air chambers in them, so they do not suffer from large-scale pressure effects. However, they do have to cope with microscopic effects on proteins and membranes; see OUR PRESSURE RESEARCH below. |

| Return to Top | Return to Contents Homepage |

| IV.B. OUR DEEP-SEA RESEARCH |

| 1. PRESSURE ADAPTATIONS High pressure traps water molecules at a high density around charged molecules, interfering with critical binding events in cells involving proteins. Dr. Joe Siebenaller of L.S.U. and other researchers have found that many proteins in deep-sea fishes somehow compensate for this effect. However, not all deep-sea proteins are pressure resistant. Pressure also makes membranes more rigid, impairing transport functions, etc. Researchers have found that deep-sea organisms have unsaturated lipids in their membranes to "loosen" them up. Unsaturated lipids (an example is vegetable oil) have mixed C-C single bonds and C=C double-bonds that prevent the lipid chains from stacking tightly together, making the lipid or fat more liquidy. In contrast, saturated lipids have all C-C single bonds that stack together, making the lipid or fat more rigid (an example is butter). In my laboratory, we have found that deep-sea fishes and some invertebrates have the highest known levels of trimethylamine oxide or TMAO (see below). This is a common compound in many marine animals, used to help maintain water balance against the high salinity of the sea. If your computer had "RealOdor" or "QuickSmell" technology, you'd recognize TMAO--it and its breakdown product, TMA, are what makes marine animals smell fishy. TMAO is also a stabilizer of proteins (helping these biological molecules remain functional when perturbed), and we have extensive evidence (see example below) that it may be very high in these animals in order to help pressure-sensitive proteins overcome pressure inhibition (perhaps by helping to remove dense water from charged molecules). See references by Gillett, Kelly, Samerotte and Yancey below, New Scientist news story (1999), and BBC story (2014) about a possible depth limit for fishes based on TMAO. --We analyzed deep clams from cold seeps and found they have an unusual compound first reported by Alberic and Boulegue in 1990: serine-phosphoethanolamine-X (where X is an unknown). We discovered that this compound increases with depth in clams from 1100 to 6400m depth. It may help protect proteins from pressure effects (Fiess et al.). |

|||||

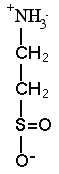

| RIGHT: Structure of TMAO; and GRAPH of Effects of TMAO on Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) from a rattail (=grenadier) fish. After 8 hr at 1000 atm, this enzyme in water lost much of its activity, but with TMAO it lost much less. LDH is an enzyme that is crucial for burst activity in muscles. |

RIGHT: Examples

of laboratory high-pressure devices that we've used. |

||||

Hypotaurine |

2. SULFIDE ADAPTATIONS We discovered the sulfur compound methyltaurine as a dominant osmolyte in Lamellibrachia seep tubeworms. Its function is unknown, but as a methylamine, it may help counteract pressure effects (Yin et al. 2000). REFERENCES: |

|

|

||

|

3. Protein Contents and Anatomy of Midwater (Mesopelagic) Fishes (1980s) We discovered that the muscles of midwater fishes (such as viperfish) have extremely low protein contents: 5-10% protein, compared to 15-20% in a surface (epipelagic fish, such as a tuna). We also discovered that some of these deep fish have an unusual buoyant gelatinous layer around their spines or under their skins:

|

| Return to top | Return to Contents Homepage |