| MAMMALS -- CALIFORNIA, OREGON: we often see small marine mammals while leaving port on research ships and tour boats. At sea, whales, dolphins and porpoises are often seen, sometimes in the hundreds! | |||

Sea otters at Moss Landing, CA (above, below; 2012) |

Sealions, Moss Landing CA (2012) |

Dahl's porpoises  Heather Groshong's 35mm film images (2001; off Eureka, CA) |

Tara Goldsmith's 35mm film images (1996) |

Blue whale tail (Monterey Bay, CA, 2012) |

Humpback feeding (Monterey Bay, CA, 2012) |

Humpbacks lunge-feeding (Monterey Bay, CA, 2012) |

|

| VIDEOS of WILD PORPOISES LEAPING, TAILSLAPPING off Newport, OR |

| MISCELLANEOUS--1. CALIFORNIA, OREGON: various shallow-water animals seen from or caught with research ships at sea. | ||||

. . . .

|

|

|

|

|

|

Large jellies in huge numbers

invade Monterey Bay in Aug-Sept. 2009 |

Pelagic barnacles drift in the

currents with their own float! |

Sailing Velella

[colonial hydrozoan] |

Leptocephalus of eel

(juvenile/larval) |

Pelagic snail? Or?

(heteropod?) |

| 2. SOUTH FLORIDA: various shallow-water animals seen from shore, tour boat or kayak. | ||||

Manatee (Key Largo, 2011) |

Manatee (Everglades, 2012) |

Portuguese Man O' War (Florida Keys, 2011) |

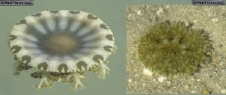

Cassiopeia (Upside-Down Jelly; often lies inverted to obtain light for its algal symbionts) Key Largo, 2011 |

Tunicates on mangrove roots Key Largo, 2011 |

Osprey (Everglades, 2012) |

Osprey (Everglades, 2012) |

Saltwater crocodile (Everglades, 2012) |

Reef fish with tumor Dry Tortugas 2012 |

Pelican in flight Everglades 2012 |

LINKS: Here are pages with pictures, sounds of and descriptions of

dolphins and whales:

|

| NEWS ON NAVAL SONAR AND CETACEANS: Nov. 2008: The Supreme Court rules in favor of the Navy, allowing continued testing of their sonar that may be disturbing marine mammals--see below May 2003: New evidence shows that Navy sonar disturbs orcas and porpoises in the wild--see the SoundNet article. Earlier news: In Dec. 2001, the Navy finally admitted that its new low-frequency sonar--described below--caused the beaching of 16 whales in the Bahamas in Mar. 2000. Six animals died on the beach, and they all had hemorrhaging around their ears. In the Jan. 26 2001 issue of Science (p. 576) and the Mar. 5, 1998 issue of Nature (p.29), evidence is presented that strongly links the US Navy's testing of its Low Frequency Active Sonar (LFAS) with mass beaching and dying of whales. The 1998 study shows that precisely during the spring 1996 testing of LFAS near Greece, beachings of beaked whales jumped almost 20-fold in the exact area of testing. While not 100% conclusive, the study makes it very possible that this extremely loud sound device, designed to detect quiet submarines, interferes with the sensitive sound-making and hearing of whales. The 2001 article discusses research on human sonar and beaching incidents in the Bahamas. For more information, see San Francisco Medical Foundation's LFAS Site, and the LFAS Issues Site. |

| WHALE BEACHING: why DO whales often beach themselves, usually dying

in the process? (See CNN for recent news stories and videos of beached

whales: California

Grey Whales, Australian

Sperm Whales) (and NY Times on East

Coast Dolphins). There are many hypotheses (e.g., confusion by disease;

inability of their sonar to detect gently sloping sand) but no clear answers.

An hypothesis of mine is that whales may run up onto beaches when a primitive

urge to return to land is triggered by certain dangers. After all, whales'

immediate ancestors were semi-terrestrial (clearly shown in the fossil record).

They possibly went to sea to feed and to land to escape danger. Other marine

mammals, even those awkward on land--seals, seal lions for example--still

do this, because isolated beaches have fewer large predators than the ocean.

And some researchers suggest that sunbathing in the air helps seals to heal

wounds and kill skin parasites. Whales ancestors may have done the same.

Perhaps deep in their brains is a remnant of this behavior, triggered only

by new or extreme dangers that their normal behaviors and higher brain centers

cannot cope with. Since this beaching behavior is not adaptive to modern, non-terrestrial whales, it could be an example of an evolutionary vestige: a once-useful feature no longer of value. We humans have many such vestigal behaviors; examples include the raising of our few hairs when we are cold or scared (useful in a hairy animal like a cat to trap warm air or to look big, but not useful in us); and our craving for sweet and fat (once useful in times of food scarcity, but detrimental in societies with plentiful food). (AND--why do humans like to be in water so much?) |